Juneteenth and the City of Houston

The actual announcement of Juneteenth was probably more bureaucratic than dramatic. Whether Union Major General Gordon Granger proclaimed freedom to gathered slaves from the balcony of an island city mansion – as oral tradition contends – or merely in tiny type on the front page of the city’s newspaper, the effect was nonetheless electric.

As such, its legacy has endured through the decades in a never-fading outpouring of human joy as well as pain. For Texas slaves, the promise of Abraham Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, meant to be ratified on New Year's Day 1863, languished unfulfilled until Granger arrived in Galveston months after the Confederacy's collapse.

On June 19, 1865, he issued a series of directives to re-establish civil government for the rebel cotton port. General Order No. 3 was the blockbuster. It mandated the immediate liberation of slaves, demanding that henceforth they be treated as autonomous wage workers.

Within days, African-Americans gathered in towns and hamlets for picnics, dances and speeches filled with the wonderment of new life. In the Port of Galveston and along the Brazos River, newly freed men and women began to stir.

Many who had labored in Galveston, or on the Brazos Valley's cotton and sugar plantations – where as much as half of the total population had been held in bondage – streamed in to Houston, many following the San Felipe Road. In Houston, then a town of little more than 9,000 residents, the old road became Dallas Street. Dallas Street, in turn, became the heartbeat of Freedmen's Town, a city-within-a-city built by freed slaves and their descendants.

Less than one year after Granger issued his decrees, the first black settlers had established homes near Buffalo Bayou. Within decades, the new Fourth Ward neighborhood centered on Dallas, Taft and Travis streets became home to a vibrant cross-section of humanity. Freedmen's Town filled with doctors, blacksmiths, lawyers, brick makers, barbers, teachers and more than a few men of God. By the 19th century's end, 95 percent of black-owned businesses were located there. By 1910, Freedmen's Town was home to approximately 6,000 of the city's 79,000 residents. Almost from the beginning, Freedmen's Town was a center for business, education and religion.

Founded in 1866, Antioch Missionary Baptist Church loomed large in the community's life. Guided by its visionary Virginia-born pastor, the Rev. John Henry "Jack" Yates, Antioch ministered both to spiritual and material needs. Yates was a staunch advocate for freedmen, urging self-reliance and home ownership and pushing for expansion of educational opportunities. An academy he founded provided youngsters a firm grounding for fulfilling, productive lives and laid the foundation for today's Texas Southern University.

The preacher and his peers were serious community-builders, but by no means were they all work and no play. In 1872, Yates joined with the Rev. Elias Dibble of Trinity Episcopal Methodist Church and politician Richard Allen to raise money for a community park. Close to $1,000 was collected through a host of strategies, including assessing fees to future park concessionaires, and by summer of that year a 10-acre parcel in the heart of the Third Ward was in the hands of Houston's African-American citizens.

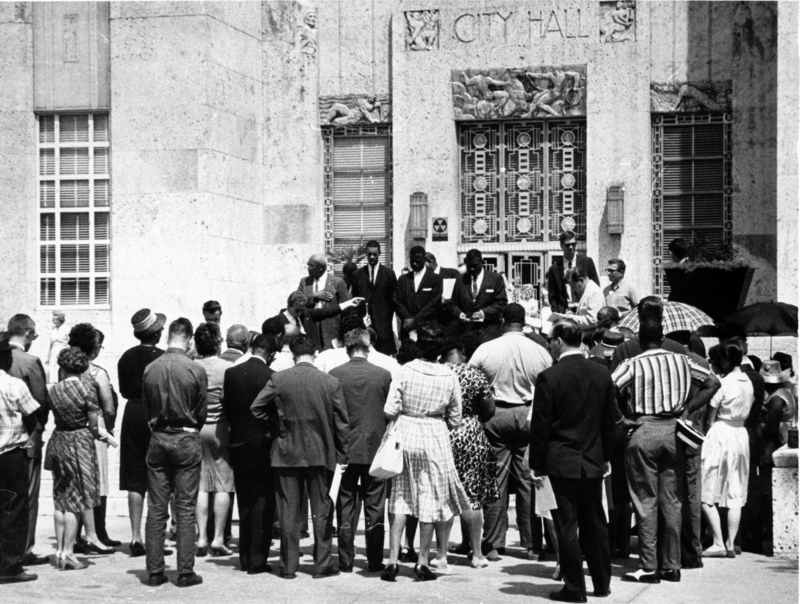

The park – the very first open to Houston blacks – was named Emancipation Park in homage to Granger's immortal General Order No. 3. Older residents interviewed in the 1970s recalled the park as the center of community life. Bordered by a tall wooden fence, the park featured a racetrack and twin dance halls. On summer evenings, it was the venue for the screening of free, community movies, and, sometimes in winter, it served as off-season quarters for a circus. And on Juneteenth, the park became a center of jollity as thousands, fresh from parading through downtown and neighborhood streets, arrived for picnics, speeches and a night of dancing. High spirits blanketed the city as churches, social clubs and individual families hosted their own celebrations.

As part of the video projects that have accompanied Juneteenth at Miller Theatre, Houstonians have shared their personal memories of the commemoration. They are telling. In a neighborhood known as Pleasantville on Houston's far east side, Norma Bradley's family geared up for the holiday days in advance – ordering up country sausage from Weimer, watermelons from Hempstead and pound cakes from Grandma. "It was like a spiritual holiday," Norma recalled. "We had Christmas, Easter and the 19th of June."

Sandra Hines' parents greeted friends, neighbors and relatives at their Houston home in Sunnyside with the homemade cakes and pies and giant ice-filled tubs of red soda water, the royal elixir of the Juneteenth fete. "They were kind to their neighbors, their family, to anyone," she said.

Juneteenth, recalled another longtime Houston resident, Christopher Spellmon, eclipsed the Fourth of July. "Our teaching was that the Fourth of July wasn't actually our holiday," he said. "Juneteenth was our holiday."

For many, the day was steeped in religious significance. Remembering events at Emancipation Park, Ruby Sanders Mosley said of the celebrations of her youth. "The dance hall was upstairs; the stands with soda water, ice cream and those things was downstairs. But the tabernacle for services on the 19th were over on the other side. That whole day was spent serving God."

Years passed, and the holiday was embraced by non-Texans – June 19th now is celebrated in more than 40 states – and by non-blacks. Though loved and widely observed, Texas' premier black holiday had to wait more than a century before it became official. The legislative battled to make Juneteenth an official state holiday, waged by Houston state Rep. Al Edwards, was arduous – and lonely. "My brother," said Redick Edwards, "was a lone wolf in the wilderness." Despite initial indifference, even among African-American lawmakers, Edwards' passionate campaign was victorious in 1979. Juneteenth debuted as an official holiday the following year.

Later, Representative Edwards attributed the success to support from every racial or ethnic group, every gender. "I can't imagine too many things more important to the human race – not just blacks – than the coming out of slavery into freedom."

U.S. Rep. Al Green of Houston underscored the holiday's importance. "There are great dates in the lives of people," he said. "For every individual, your birthday is an important day. It's the day you gained the breath of life... Then, after your birthday, I think it's important to celebrate the day that caused you to understand what freedom was for your ancestors."

"These are the two great days in the lives of the people."

Allan Turner and Pat Jasper, 2017